In the world of network security, it pays to always remember that many (if not most!) security bugs start off their lives as seemingly innocuous “regular” bugs, and it’s only by diligently considering how aberrant behavior – say, incorrect results returned for particular inputs or a mere “stability issue” that turns out to actually be a use-after-free causing the observed crashes – could be abused by determined malicious actors that the underlying security implications become obvious. This has great benefits: for instance, it can be argued that it wasn’t until Microsoft started taking BSoDs that could be triggered by unprivileged users seriously, recognizing them for the open backdoors most of them were, that Windows actually became usably stable.

Of course, then there are the bugs that have such blatantly obvious security implications that it would be hard to qualify them as wolves in sheep’s clothing. Someone encountering such a bug, even if not particularly security-minded, would be forced to immediately recognize the risk they pose even if only because they have to deal with its consequences. This post is about such a security bug that I encountered in the same vein as many others in the past: simply trying to do something completely unrelated and running into a vulnerability that made the task at hand that much harder.

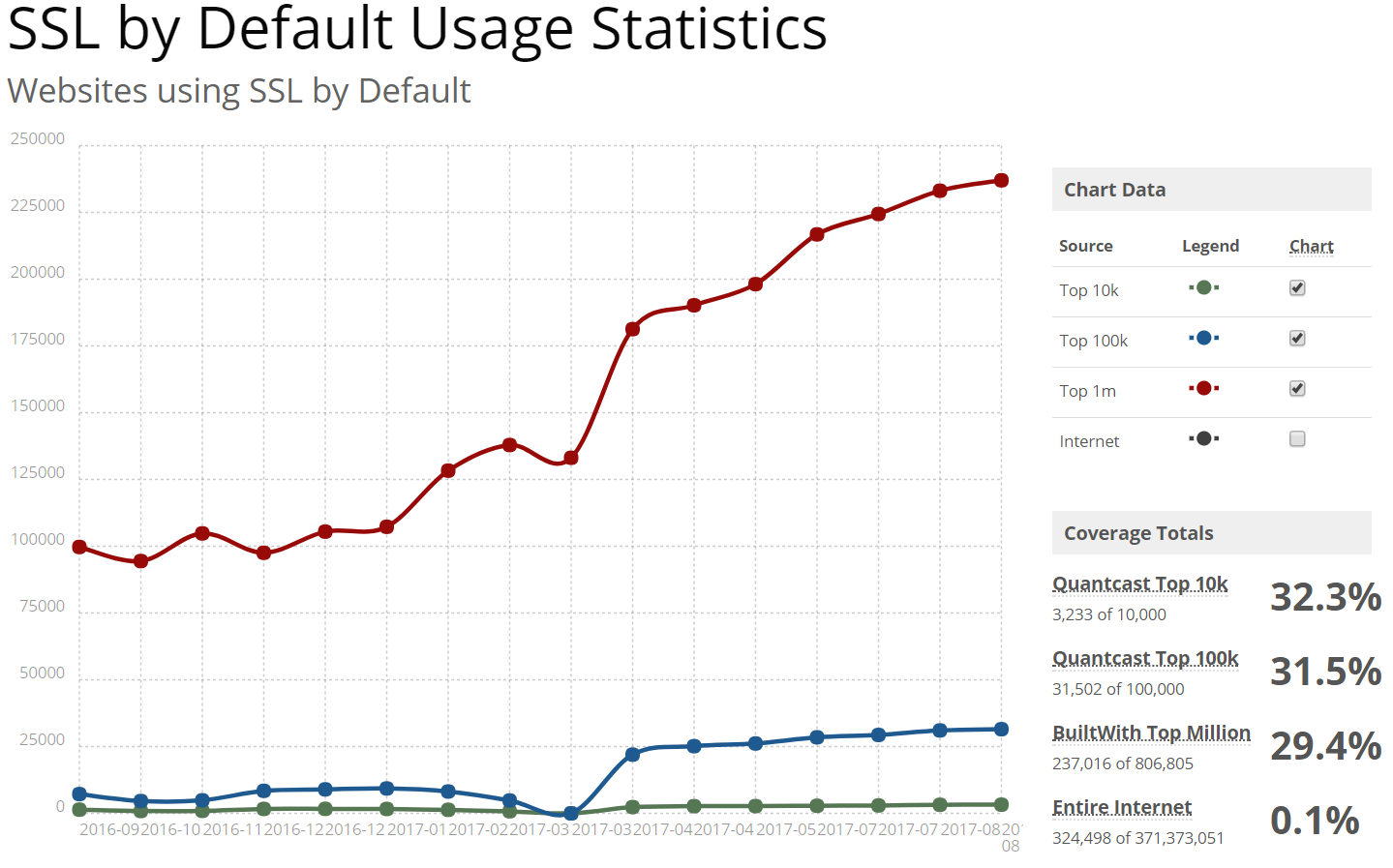

HTTPS is the future and the future is (finally) here. Secure HTTP requests that provide end-to-end encryption between the client making the request and the server providing it with the requested content is finally making some headway, with almost a third of the top one million sites on the internet serving content over SSL, as of August 2017:

HTTPS is the future and the future is (finally) here. Secure HTTP requests that provide end-to-end encryption between the client making the request and the server providing it with the requested content is finally making some headway, with almost a third of the top one million sites on the internet serving content over SSL, as of August 2017:

1Password and LastPass are probably the two best known names in the password storage business, both having been around from 2006 and 2008, respectively. Back in 2008, the internet was a very different place than it is today, especially when it comes to security. Since then, a lot has changed and the world has (hopefully) become a more security-conscious place – and security experts have come to a consensus on a lot of practices and approaches when it comes to encryption and the proper handling of sensitive data.

1Password and LastPass are probably the two best known names in the password storage business, both having been around from 2006 and 2008, respectively. Back in 2008, the internet was a very different place than it is today, especially when it comes to security. Since then, a lot has changed and the world has (hopefully) become a more security-conscious place – and security experts have come to a consensus on a lot of practices and approaches when it comes to encryption and the proper handling of sensitive data. SecureStore

SecureStore If you’re a developer working on or maintaining a website catering to the general public, chances are you’ve implemented some form of password reset via security question-and-answer into your site. How are you storing the answers to these questions in your database? Are you encrypting them? Storing the (hopefully cryptographic, salted) hashes? Or are you storing them plain text?

If you’re a developer working on or maintaining a website catering to the general public, chances are you’ve implemented some form of password reset via security question-and-answer into your site. How are you storing the answers to these questions in your database? Are you encrypting them? Storing the (hopefully cryptographic, salted) hashes? Or are you storing them plain text?