Heads-up: An update to this article has been posted.

There have been a lot of complaints about both the competency and the logic behind the latest Epstein archive release by the DoJ: from censoring the names of co-conspirators to censoring pictures of random women in a way that makes individuals look guiltier than they really are, forgetting to redact credentials that made it possible for all of Reddit to log into Epstein’s account and trample over all the evidence, and the complete ineptitude that resulted in most of the latest batch being corrupted thanks to incorrectly converted Quoted-Printable encoding artifacts, it’s safe to say that Pam Bondi’s DoJ did not put its best and brightest on this (admittedly gargantuan) undertaking. But the most damning evidence has all been thoroughly redacted… hasn’t it? Well, maybe not.

I was thinking of writing an article on the mangled quoted-printable encoding the day this latest dump came out in response to all the misinformed musings and conjectures that were littering social media (and my dilly-dallying cost me, as someone beat me to the punch), and spent some time searching through the latest archives looking for some SMTP headers that I could use in the article when I came across a curious artifact: not only were the emails badly transcoded into plain text, but also some binary attachments were actually included in the dumps in their over-the-wire Content-Transfer-Encoding: base64 format, and the unlucky intern that was assigned to the documents in question didn’t realize the significance of what they were looking at and didn’t see the point in censoring seemingly meaningless page after page of hex content!

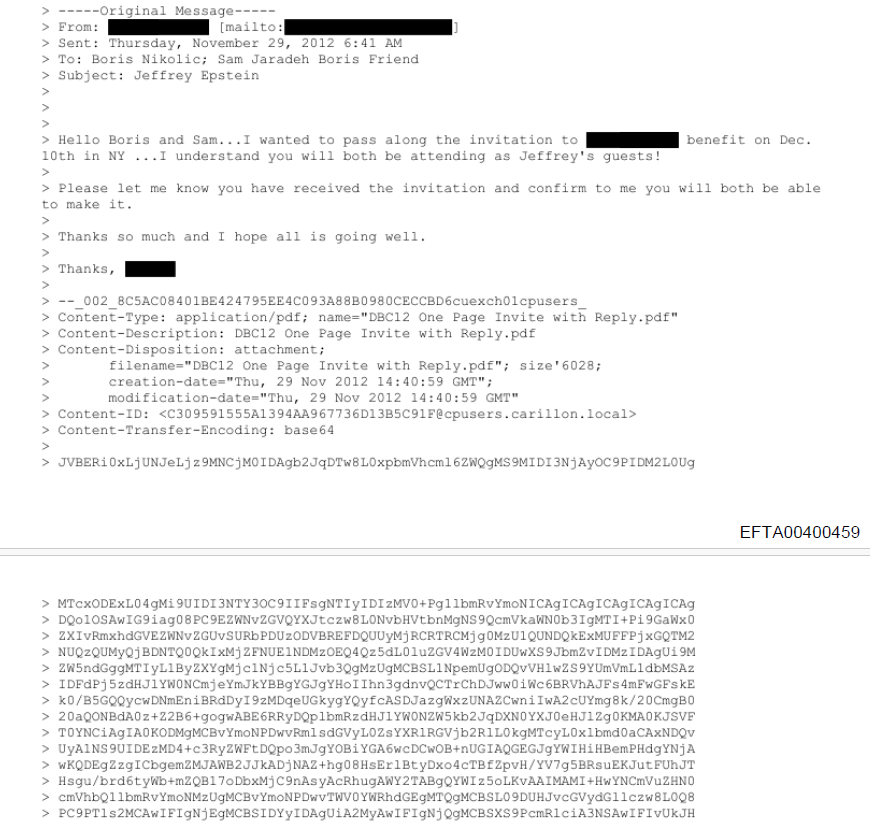

Just take a look at EFTA00400459, an email from correspondence between (presumably) one of Epstein’s assistants and Epstein lackey/co-conspirator Boris Nikolic and his friend, Sam Jaradeh, inviting them to a ████████ benefit:

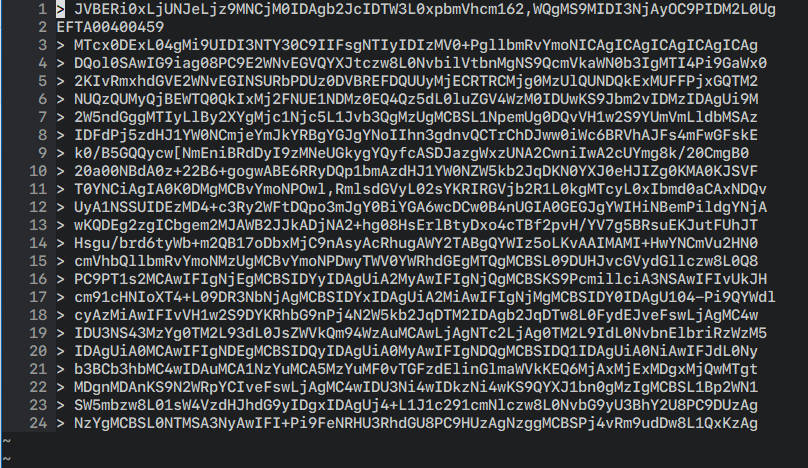

Those hex characters go on for 76 pages, and represent the file DBC12 One Page Invite with Reply.pdf encoded as base64 so that it can be included in the email without breaking the SMTP protocol. And converting it back to the original PDF is, theoretically, as easy as copy-and-pasting those 76 pages into a text editor, stripping the leading > bytes, and piping all that into base64 -d > output.pdf… or it would be, if we had the original (badly converted) email and not a partially redacted scan of a printout of said email with some shoddy OCR applied.

If you tried to actually copy that text as digitized by the DoJ from the PDF into a text editor, here’s what you’d see:

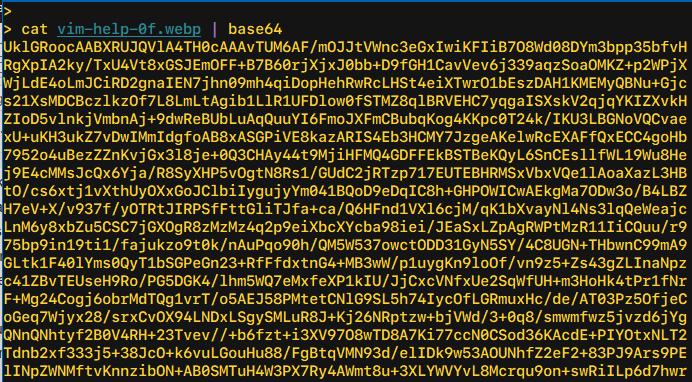

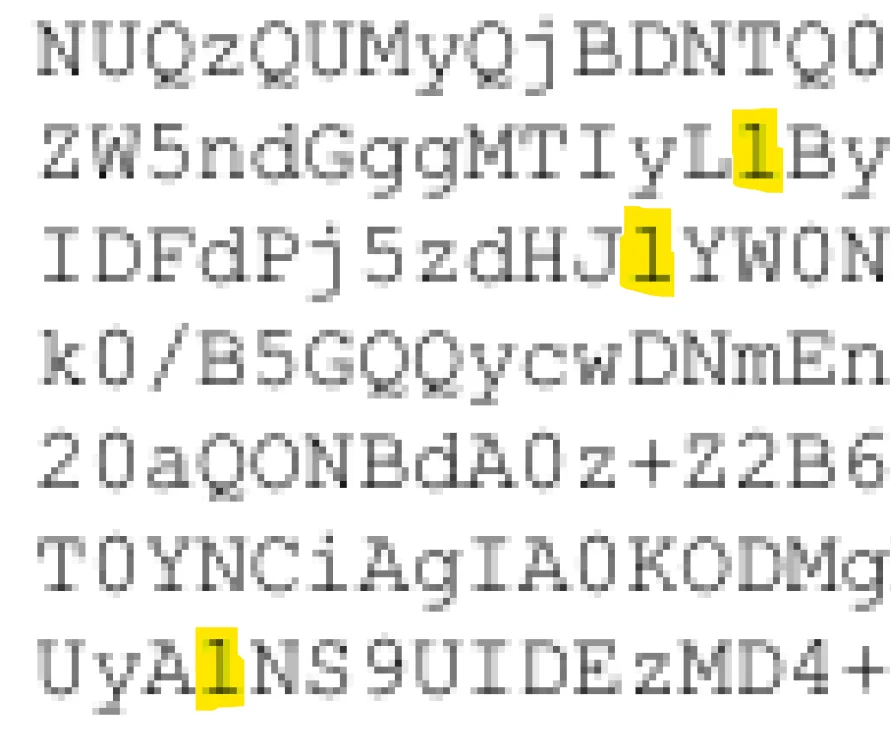

You can ignore the EFTA00400459 on the second line; that (or some variant thereof) will be interspersed into the base64 text since it’s stamped at the bottom of every page to identify the piece of evidence it came from. But what else do you notice? Here’s a hint: this is what proper base64 looks like:

Notice how in this sample everything lines up perfectly (when using a monospaced font) at the right margin? And how that’s not the case when we copied-and-pasted from the OCR’d PDF? That’s because it wasn’t a great OCR job: extra characters have been hallucinated into the output, some of them not even legal base64 characters such as the , and [, while other characters have been omitted altogether, giving us content we can’t use:1

> pbpaste \

| string match -rv 'EFTA' \

| string trim -c " >" \

| string join "" \

| base64 -d >/dev/null

base64: invalid input

I tried the easiest alternative I had at hand: I loaded up the PDF in Adobe Acrobat Pro and re-ran an OCR process on the document, but came up with even worse results, with spaces injected in the middle of the base64 content (easily fixable) in addition to other characters being completely misread and butchered – it really didn’t like the cramped monospace text at all. So I thought to do it manually with tesseract, which, while very far from state-of-the-art, can still be useful because it lets you do things like limit its output to a certain subset of characters, constraining the field of valid results and hopefully coercing it into producing better results.

Only one problem: tesseract can’t read PDF input (or not by default, anyway). No problem, I’ll just use imagemagick/ghostscript to convert the PDF into individual PNG images (to avoid further generational loss) and provide those to tesseract, right? But that didn’t quite work out, they seem (?) to try to load and perform the conversion of all 76 separate pages/png files all at once, and then naturally crash on too-large inputs (but only after taking forever and generating the 76 (invalid) output files that you’re forced to subsequently clean up, of course):

> convert -density 300 EFTA00400459.pdf \

-background white -alpha remove \

-alpha off out.png

convert-im6.q16: cache resources exhausted `/tmp/magick-QqXVSOZutVsiRcs7pLwwG2FYQnTsoAmX47' @ error/cache.c/OpenPixelCache/4119.

convert-im6.q16: cache resources exhausted `out.png' @ error/cache.c/OpenPixelCache/4119.

convert-im6.q16: No IDATs written into file `out-0.png' @ error/png.c/MagickPNGErrorHandler/1643.

So we turn to pdftoppm from the poppler-utils package instead, which does indeed handle each page of the source PDF separately and turned out to be up to the task, though incredibly slow:

> pdftoppm -png -r 300 EFTA00400459.pdf out.png

After waiting the requisite amount of time (and then some), I had files out-01.png through out-76.png, and was ready to try them with tesseract:

for n in (printf "%02d\n" (seq 1 76))

tesseract out-$n.png output-$n \

--psm 6 \

-c tessedit_char_whitelist='>'ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789+/= \

-c load_system_dawg=0 \

-c load_freq_dawg=0

end

The above fish-shell command instructs tesseract(1) to assume the input is a single block of text (the --psm 6 argument) and limit itself to decoding only legal base64 characters (and the leading > so we can properly strip it out thereafter). My original attempt included a literal space in the valid char whitelist, but that gave me worse results: the very badly kerned base64 has significant apparent spacing between some adjacent characters (more on this later) and that caused tesseract to both incorrectly inject spaces (bad but fixable) and also possibly affect how it handled the character after the space (worse).

Unfortunately, while tesseract gave me slightly better output than either the original OCR’d DoJ text or the (terrible) Adobe Acrobat Pro OCR results, it too suffered from poor recognition and gave me very inconsistent line lengths… but it also suffered from something that I didn’t really think a heuristic-based, algorithm-driven tool like tesseract would succumb to, as it was more reminiscent of how first-generation LLMs would behave: in a few places, it would only read the first dozen or so characters on a line then leave the rest of the line blank, then pick up (correctly enough) at the start of the next line. Before I saw how generally useless the OCR results were and gave up on tesseract, I figured I’d just manually type out the rest of the line (the aborted lines were easy enough to find, thanks to the monospaced output), and that was when I ran into the real issue that took this from an interesting challenge to being almost mission impossible.

A note from the author I do this for the love of the game and in the hopes of hopefully exposing some bad people. But I do have a wife and small children and this takes me away from my work that pays the bills. If you would like to support me on this mission, you can make a contribution here.

I mentioned earlier the bad kerning, which tricked the OCR tools into injecting spaces where there were supposed to be none, but that was far from being the worst issue plaguing the PDF content. The real problem is that the text is rendered in possibly the worst typeface for the job at hand: Courier New.

If you’re a font enthusiast, I certainly don’t need to say any more – you’re probably already shaking with a mix of PTSD and rage. But for the benefit of everyone else, let’s just say that Courier New is… not a great font. It was a digitization of the venerable (though certainly primitive) Courier fontface, commissioned by IBM in the 1950s. Courier was used (with some tweaks) for IBM typewriters, including the IBM Selectric, and in the 1990s it was “digitized directly from the golf ball of the IBM Selectric” by Monotype, and shipped with Windows 3.1, where it remained the default monospace font on Windows until Consolas shipped with Windows Vista. Among the many issues with Courier New is that it was digitized from the Selectric golf ball “without accounting for the visual weight normally added by the typewriter’s ink ribbon”, which gives its characteristic “thin” look. Microsoft ClearType, which was only enabled by default with Windows Vista, addressed this major shortcoming to some extent, but Courier New has always struggled with general readability… and more importantly, with its poor distinction between characters.

While not as bad as some typewriter-era typefaces that actually reused the same symbol for 1 (one) and l (ell), Courier New came pretty close. Here is a comparison between the two fonts when rendering these two characters, only considerably enlarged:

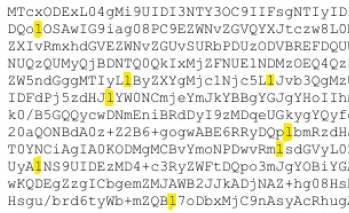

The combination of the two faults (the anemic weights and the even less distinction between 1 and l as compared to Courier) makes Courier New a terrible choice as a programming font. But as a font used for base64 output you want to OCR? You really couldn’t pick a worse option! To add fuel to the fire, you’re looking at SVG outlines of the fonts, meticulously converted and preserving all the fine details. But in the Epstein PDFs released by the DoJ, we only have low-quality JPEG scans at a fairly small point size. Here’s an actual (losslessly encoded) screenshot of the DoJ text at 100% – I challenge you to tell me which is a 1 and which is an l in the excerpt below:

It’s not that there isn’t any difference between the two, because there is. And sometimes you get a clear gut feeling which is which – I was midway through manually typing out one line of base64 text when I got stuck on identifying a one vs ell… only to realize that, at the same time, I had confidently transcribed one of them earlier that same line without even pausing to think about which it was. Here’s a zoomed-in view of the scanned PDF: you can clearly see all the JPEG DCT artifacts, the color fringing, and the smearing of character shapes, all of which make it hard to properly identify the characters. But at the same time, at least in this particular sample, you can see which of the highlighted characters have a straight serif leading out the top-left (the middle, presumably an ell) and which of those have the slightest of strokes/feet extending from them (the first and last, presumably ones). But whether that’s because that’s how the original glyph appeared or it’s because of how the image was compressed, it’s tough to say:

But that’s getting ahead of myself: at this point, none of the OCR tools had actually given me usable results, even ignoring the very important question of l vs 1. After having been let down by one open source offering (tesseract) and two commercial ones (Adobe Acrobat Pro and, presumably, whatever the DoJ used), I made the very questionable choice of writing a script to use yet another commercial offering, this time Amazon/AWS Textract, to process the PDF. Unfortunately, using it directly via the first-party tooling was (somewhat) of a no-go as it only supports smaller/shorter inputs for direct use; longer PDFs like this one need to be uploaded to S3 and then use the async workflow to start the recognition and poll for completion.

Amazon Textract did possibly the best out of all the tools I tried, but its output still had obvious line length discrepancies – albeit only one to two characters or so off on average. I decided to try again, this time blowing up the input 2x (using nearest neighbor sampling to preserve sharp edges) as a workaround for Textract not having a tunable I could set to configure the DPI the document is processed at, though I worried all inputs could possibly be prescaled to a fixed size prior to processing once more:2

> for n in (printf "%02d\n" (seq 01 76))

convert EFTA00400459-$n.png -scale 200% \

EFTA00400459-$n"_2x".png; or break

end

> parallel -j 16 ./textract.sh {} ::: EFTA00400459-*_2x.png

These results were notably better, and I’ve included them in an archive, but some of the pages scanned better than others. Textract doesn’t seem to be 100% deterministic from my brief experience with it, and their features page does make vague or unclear mentions to “ML”, though it’s not obvious when and where it kicks in or what it exactly refers to, but that could explain why a couple of the pages (like EFTA00400459-62_2x.txt) are considerably worse than others, even while the source images don’t show a good reason for that divergence.

With the Textract 2x output cleaned up and piped into base64 -i (which ignores garbage data, generating invalid results that can still be usable for forensic analysis), I can get far enough to see that the PDF within the PDF (i.e. the actual PDF attachment originally sent) was at least partially (de)flate-encoded. Unfortunately, PDFs are binary files with different forms of compression applied; you can’t just use something like strings to extract any usable content. qpdf(1) can be (ab)used to decompress a PDF (while leaving it a PDF) via qpdf --qdf --object-streams=disable input.pdf decompressed.pdf, but, predictably, this doesn’t work when your input is garbled and corrupted:

> qpdf --qdf --object-streams=disable recovered.pdf decompressed.pdf

WARNING: recovered.pdf: file is damaged

WARNING: recovered.pdf: can't find startxref

WARNING: recovered.pdf: Attempting to reconstruct cross-reference table

WARNING: recovered.pdf (object 34 0, offset 52): unknown token while reading object; treating as string

WARNING: recovered.pdf (object 34 0, offset 70): unknown token while reading object; treating as string

WARNING: recovered.pdf (object 34 0, offset 85): unknown token while reading object; treating as string

WARNING: recovered.pdf (object 34 0, offset 90): unexpected >

WARNING: recovered.pdf (object 34 0, offset 92): unknown token while reading object; treating as string

WARNING: recovered.pdf (object 34 0, offset 116): unknown token while reading object; treating as string

WARNING: recovered.pdf (object 34 0, offset 121): unknown token while reading object; treating as string

WARNING: recovered.pdf (object 34 0, offset 121): too many errors; giving up on reading object

WARNING: recovered.pdf (object 34 0, offset 125): expected endobj

WARNING: recovered.pdf (object 41 0, offset 9562): expected endstream

WARNING: recovered.pdf (object 41 0, offset 8010): attempting to recover stream length

WARNING: recovered.pdf (object 41 0, offset 8010): unable to recover stream data; treating stream as empty

WARNING: recovered.pdf (object 41 0, offset 9616): expected endobj

WARNING: recovered.pdf (object 41 0, offset 9616): EOF after endobj

qpdf: recovered.pdf: unable to find trailer dictionary while recovering damaged file

Between the inconsistent OCR results and the problem with the l vs 1, it’s not a very encouraging situation. To me, this is a problem begging for a (traditional, non-LLM) ML solution, specifically leveraging the fact that we know the font in question and, roughly, the compression applied. Alas, I don’t have more time to lend to this challenge at the moment, as there are a number of things I set aside just in order to publish this article.

So here’s the challenge for anyone I can successfully nerdsnipe:

- Can you manage to recreate the original PDF from the

Content-Transfer-Encoding: base64output included in the dump? It can’t be that hard, can it? - Can you find other attachments included in the latest Epstein dumps that might also be possible to reconstruct? Unfortunately, the contractor that developed the full-text search for the Department of Justice did a pretty crappy job and full-text search is practically broken even accounting for the bad OCR and wrangled quoted-printable decoding (malicious compliance??); nevertheless, searching for

Content-Transfer-Encodingandbase64returns a number of results – it’s just that, unfortunately, most are uselessly truncated or only the SMTP headers from Apple Mail curiously extracted.

I have uploaded the original EFTA00400459.pdf from Epstein Dataset 9 as downloaded from the DoJ website to the Internet Archive, as well as the individual pages losslessly encoded to WebP images to save you the time and trouble of converting them yourself. If it’s of any use to anyone, I’ve also uploaded the very-much-invalid Amazon Textract OCR text (from the losslessly 2x’d images), which you can download here.

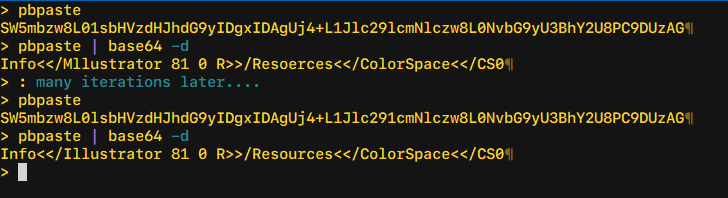

Oh, and one final hint: when trying to figure out 1 vs l, I was able to do this with 100% accuracy only via trial-and-error, decoding one line of base64 text at-a-time, but this only works for the plain-text portions of the PDF (headers, etc). For example, I started with my best guess for one line that I had to type out myself when trying with tesseract, and then was able to (in this case) deduce which particular 1s or ls were flipped:

> pbpaste SW5mbzw8L01sbHVzdHJhdG9yIDgxIDAgUj4+L1Jlc29lcmNlczw8L0NvbG9yU3BhY2U8PC9DUzAG > pbpaste | base64 -d Info<</Mllustrator 81 0 R>>/Resoerces<</ColorSpace<</CS0 > > # which I was able to correct: > > pbpaste SW5mbzw8L0lsbHVzdHJhdG9yIDgxIDAgUj4+L1Jlc291cmNlczw8L0NvbG9yU3BhY2U8PC9DUzAG > pbpaste | base64 -d Info<</Illustrator 81 0 R>>/Resources<</ColorSpace<</CS0

…but good luck getting that to work once you get to the flate-compressed sections of the PDF.

I’ll be posting updates on Twitter @mqudsi, and you can reach out to me on Signal at mqudsi.42 if you have anything sensitive you would like to share. You can join in the discussion on Hacker News or on r/netsec. Leave a comment below if you have any ideas/questions, or if you think I missed something!

A note from the author I do this for the love of the game and in the hopes of hopefully exposing some bad people. But I do have a wife and small children and this takes me away from my work that pays the bills. If you would like to support me on this mission, you can make a contribution here.

UPDATE

This was solved last night (February 6, 2026). You can read about it in the follow-up to this article.

In case you’re wondering, the shell session excerpts in this article are all in

fish, which I think is a good fit for string wrangling because of itsstringbuiltin with extensive operations with a very human-readable syntax (at least compared toperlorawk, the usual go-tos for string manipulation), and it lets you compose multiple operations as separate commands while not devolving to performing pathologically because no external commands arefork/exec‘d because of its builtin nature. And I’m not just saying that because of the blood, sweat, and tears I’ve contributed to the project. ↩I didn’t want to convert the PNGs back to a single PDF as I didn’t want any further loss in quality. ↩

By playing with the curves using photopea I’m able to improve the readability a bit.

I’m applying the curve layer only at the top of the character

https://full.ouplo.com/1a/6/ECnz.png

And I use a “sketch” curve to precisely darken the selection

https://full.ouplo.com/1a/6/7msk.png

Might also be interesting to extract small jpegs from all the ambiguous “1/l” and then make a website to crowd source the most likely character, like captchas.

An alternative approach — captcha style:

– Divide the image into chunks like 50 characters long

– Put it on a website where anyone can type up the small amount of characters

– Reconstruct the text from the chunks

I have no doubt the masses of the internet will deliver on this one.

Oh! That’s embarrassing – the previous commenter had the exact same idea.

AND i wrote my name as “anon” — but my picture is there 💀

It’s interesting how the poorly executed encoding and redactions have turned this into more of a mystery than an actual release of information. I wonder how much more is still hidden in these corrupted files.

Perhaps this can be turned into a very tedious, monotone but mostly straight-forward task suitable for an AI assistant. The method for deciding 1 vs l would be roughly:

– Try the four possible combinations for two consecutive uncertain 1/l sites.

– Attempt a decode where every layer outputs verbose error messages and exits early on error.

– Ideally, 2 of the cases will produce identical error output. These should correspond to the two combos where the first l/1 site was chosen wrong. Congrats, you have now determined the correct value for the first of the uncertain sites.

chatgpt was excellent here … I fed it the EFTA00754474.pdf, and it quickly decoded the text portion of it.

I was able to generate images for each page of base64, apply some color curves to all of them, working now on training a tesseract model on this font, I’m pretty close, but it still has trouble with 1/l when the l is blurry, and sometimes duplicates characters, but I’m getting multiple lines with zero errors, and very good accuracy.

There is also EFTA02153691 which appears to be another email in the thread. Maybe a second source will help disambiguate some of the characters.

Make your own OCR!

This a bit more of a boring solution … but if you know the font, make a dataset analogous to MNIST and train a CNN. Then cut out every character, convert to an image and feed it to the trained CNN. I’m pretty sure it would be very quick to run and very accurate.

With the help of a good LLM, I think this could be hacked together in a few hours.

I’ve been trying to get this up and running in Azure Document intelligence, will post an update once I have more.

This little helper tool can help decode a base64 string and highlight selected sections in base64 / plain text to try different variations of ones and “l”s:

https://claude.ai/public/artifacts/4fb1c92c-a816-4b44-82b4-c2a1af1ca7bc

You can test with the code from the example above:

SW5mbzw8L01sbHVzdHJhdG9yIDgxIDAgUj4+L1Jlc291cmN1czw8L0NvbG9yU3BhY2U8PC9DUzAG

My best effort so far, basic ML with manual labelling.

Error rate seems fairly low, but there’s still random corruption.

https://pastebin.com/UXRAJdKJ

keep up with the good work, and stay safe, there are evil people out there.

There are quite a few more, see

https://www.reddit.com/r/Epstein/comments/1qu9az2/theres_unredacted_attachments_as_base64_in_some/

Is DBC12 something to do with Deutsche Bank Case or Charity?

You get better images using `pdfimages -all` rather than pdftoppm, as pdfimages just dumps out the content from the PDF with no transformations applied. It seems to provide a little better differentiation between digit one and lower case L.

PDFs themselves are structured data, so you likely can disambiguate many of the characters via surrounding context.

an simple template matching ocr works just fine..

https://github.com/KoKuToru/extract_attachment_EFTA00400459

i sucessfully extracted the PDF like this..

Validate it by printing the ocr’d lines to raster, scale to match, and overlay with a difference. It’ll show pretty clearly any otr characters that are wrong, and then just write a script to test all combinations of 1/l until it works.

The provided document is NOT the clearest version there is, this may be courier instead of courier new or just a better resoltuion, I am not sure:

https://www.justice.gov/epstein/files/DataSet%2010/EFTA02154109.pdf

thanks to Joe’s work, i was able to open the decoded base64 as a PDF. there were a couple of errors, but those can be fixed with a little knowledge of PDF file structure and 010 editor + pdftemplate. pdf structure is a little new to me, so the file is still mostly broken, but i was able to extract this:

https://pasteboard.co/ERX0CUD9ZUzP.png

What about this approach:

Take the code as is and assume all ambiguous l or 1 are ones.

Use a streaming decompressor and note the failure point. If it fails at the first one, switch that 1 to an l. Re run the streaming decompressor and note the next failure point and switch that next 1 to an l.

If this works, automate this with a custom program.

too tired to look into this, one suggestion though – since the hangup seems to be comparing an L and a 1, maybe you need to get into per-pixel measurements. This might be necessary if the effectiveness of ML or OCR models isn’t at least 99.5% for a document containing thousands of ambiguous L’s. Any inaccuracies from an ML or OCR model will leave you guessing 2^N candidates which becomes infeasible quickly. Maybe reverse engineering the font rendering by creating an *exact* replica of the source image? I trust some talented hacker will nail this in no time.

=Advise this could lead to victims disclose identity.=

I was able to recreate photo of children that Mark Epstein sent to Jeffrey Epstein. (Email: the kids – 20070912 – “boatwork2008 017” and “sept172007_003”).

I was able to recreate a very interesting email/doc file from a intelligence agency – Investigative Management. The file is “saige 6.12.06.doc” – This is page of dating website with Saige (Epstein victim) profile, with pictures. This is very interesting, Epstein had private intelligence agencies looking for his victims. He also used this intelligence to find Zach Bryan Saige boyfriend online. The most interesting thing this agency was monitoring Saige – quote from email (Re: Fw: Link) “We are undertaking some very discreet surveillance of the house in order to observe and verify Saige is really living there.” – they were monitoring victims, following, taking records. Like they are doing with this guy recently on TikTok (jan-fev/2026).

I have many more to share. Hit me on @threatintelligence@infosec.exchange

Part of your problem is that your pdftoppm command has rescaled the images from 96 dpi to 300 dpi. That’s why the command took so long, and it gave you a poor result because of the required interpolation. If you really do want to oversample, you should have made the ouput a multiple of 96, in this case 288.

But rendering the pages is not necessary. As someone else suggested, you should have just extracted the images with pdfimages. Eliminating the interpolation will give you a sharper image.

https://github.com/KoKuToru/extract_attachment_EFTA00400459

Don’t know if it is of help to anyone else here, but I’ve found I get quite good OCR for low res scans such as these with https://pypi.org/project/chrome-lens-py/

I did a search for “Content-Transfer-Encoding: base64” on the DOJ site and made a dropbox of every hit. I’d suggest sorting by size to work through them:

https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fo/zg1x4cbe3a8g7vbfyiwsr/ADzZEtN1IGaBg64i1xpChTU?rlkey=vzz0xzimm23jgr0rntemva2pa&st=wm3xkz3l&dl=0

I know nothing but happened to find my way here. I found 2 long files that are identical except they have different redactions. One is more redacted than the other. Redacted words can be seen in the second file.

In case it is useful for you in this pursuit, I wanted to share.

EFTA00723105.pdf

EFTA00750740.pdf

i have recovered the text from the pdf and am still working on the images. here’s the text – i assume these are people on the invite list for this event:

EDANA AND RAFFI ARSLANIAN

MICHELE AND TIMOTHY BARAKETT

LISA AND JEFF BLAU

ANN COLLEY

JULIE ANNE QUAY AND MATTHEW EDMONDS

LISE AND MICHAEL EVANS

EILEEN PRICE FARBMAN AND STEVEN FARBMAN

TANIA AND BRIAN HIGGINS

LAURA KRUPINSKI

MARCY AND MICHAELLE HRMAN

CHRISTINE MACK

ALICE AND LORNE MICHAELS

THALIA AND TOMMY MOTTOLA

DORE HAMMOND AND JAMES NORMILE

ANN O’MALLEY

TRISH PALIOTTA

BETH AND JASON ROSENTHAL

CAROLYN AND CURTIS SCHENKER

LESLEY AND DAVID SCHULHOF

LYNN AND STEPHAN SOLOMON

http://WWW.DUBINBREASTCENTER.ORG

DUBIN BREAST CENTER SECOND ANNUAL BENEFIT

MONDAY, DECEMBER 10,2012

HONORING ELISA PORT,MD,FACS AND THE RUTTENBERG FAMILY

MANDARIN ORIENTAL,NEW YORK CITY

i have completed pulling the text from this PDF. unfortunately, it took many hours to correct the bytes within, and many are still incorrect (resulting in images failing to load properly, wacky formatting, etc.) but i did successfully pull the names listed for this event:

EDANA AND RAFFI ARSLANIAN

MICHELE AND TIMOTHY BARAKETT

LISA AND JEFF BLAU

ANN COLLEY

JULIE ANNE QUAY AND MATTHEW EDMONDS

LISE AND MICHAEL EVANS

EILEEN PRICE FARBMAN AND STEVEN FARBMAN

TANIA AND BRIAN HIGGINS

LAURA KRUPINSKI

MARCY AND MICHAELLE HRMAN

CHRISTINE MACK

ALICE AND LORNE MICHAELS

THALIA AND TOMMY MOTTOLA

DORE HAMMOND AND JAMES NORMILE

ANN O’MALLEY

TRISH PALIOTTA

BETH AND JASON ROSENTHAL

CAROLYN AND CURTIS SCHENKER

LESLEY AND DAVID SCHULHOF

LYNN AND STEPHAN SOLOMON

http://WWW.DUBINBREASTCENTER.ORG

DUBIN BREAST CENTER SECOND ANNUAL BENEFIT

MONDAY, DECEMBER 10,2012

HONORING ELISA PORT,MD,FACS AND THE RUTTENBERG FAMILY

MANDARIN ORIENTAL,NEW YORK CITY

So here is my attempt at doing this generically. It doesn’t really work.

1. 1 and l is still really hard to distinguish. Even lowercase i get misclassified.

2. Upper and lowercase is also hard for the model to detect as it’s scale variant.

3. There are too many errors for the PDF to be decoded without some error correction and bruteforcing algorithm

https://github.com/FuouM/EpsteinYOLO-OCR

1 on improving image quality

magick input.png \

-colorspace Gray \

-resize 300% \

-unsharp 0x1 \

-contrast-stretch 0.1%x0.1% \

-deskew 40% \

prepped.png

If the scan is very noisy, try:

-median 1

2. Core Tesseract command (recommended baseline)

tesseract prepped.png output \

–oem 1 \

–psm 6 \

-c tessedit_char_whitelist=ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789+/= \

-c classify_bln_numeric_mode=1 \

-c textord_heavy_nr=1 \

-c textord_min_linesize=2.5

Please make an RSS feed.

Thank you all for your comments and suggestions!

FYI: I have written a follow-up to this article, with both the results and the nerdy details.

EFTA00400459 — Full Recovery of “DBC12 One Page Invite with Reply.pdf”

Epstein DOJ Dataset 9 — Base64 PDF Attachment Successfully Decoded

========================================================================

TL;DR

The embedded PDF attachment in EFTA00400459.pdf has been fully recovered.

It is a 2-page charity gala invitation for the Dubin Breast Center Second

Annual Benefit, held Monday, December 10, 2012, at the Mandarin Oriental

in New York City. 39 of 40 FlateDecode streams were successfully

decompressed and all text content was extracted.

========================================================================

DOCUMENT METADATA

Filename: DBC12 One Page Invite with Reply.pdf

MIME Content-Type: application/pdf

Content-Transfer: base64

Expected Size: 276,028 bytes (per MIME Content-Length)

Recovered Size: 275,971 bytes (per-line decode from KoKuToru OCR)

PDF Version: 1.5

Creator: Adobe Illustrator CS4 (v14.0)

Producer: Adobe PDF library 9.00

Creation Date: November 8, 2012, 12:40:09 PM

Modification Date: November 8, 2012, 12:40:10 PM

Title: Basic CMYK

Working Filename: DBC12_einvitation_rsvp.pdf

Pages: 2

Fonts: Gotham-Medium, Archer-BoldSC, Archer-Medium,

Avenir-Book, Avenir-Roman, Wingdings

Color Space: CMYK with PANTONE 225 C (hot pink/magenta),

PANTONE 541 M (navy blue)

Created By: Karen Hsu (per XMP metadata)

SOURCE EMAIL CONTEXT

Source Document: EFTA00400459.pdf

Dataset: Epstein DOJ Dataset 9

Source PDF Size: 11.25 MB, 76 pages

Email Date: December 3, 2012

Email Domain: cpusers.carillon.local

Associated Name: Boris Nikolic

Base64 Lines: 4,843 lines at 76 chars each

MIME Boundary: Present at line 4853

========================================================================

RECOVERED CONTENT

————————————————————————

PAGE 1 — INVITATION

————————————————————————

PLEASE JOIN

BENEFIT CO-CHAIRS

GABRIELLE AND LOUIS BACON

ALEXANDRA AND STEVEN COHEN

EVA AND GLENN DUBIN

AMY AND JOHN GRIFFIN

WENDY HAKIM JAFFE

SONIA AND PAUL TUDOR JONES II

ALLISON AND HOWARD LUTNICK

VERONIQUE AND BOB PITTMAN

BETH AND DAVID SHAW

KATHLEEN AND KENNETH TROPIN

NINA AND GARY WEXLER

JILL AND PAUL YABLON

FOR THE

DUBIN BREAST CENTER

SECOND ANNUAL BENEFIT

MONDAY, DECEMBER 10, 2012

HONORING

ELISA PORT, MD, FACS

AND

THE RUTTENBERG FAMILY

HOST

CYNTHIA MCFADDEN

SPECIAL MUSICAL PERFORMANCES

CAROLINE JONES, K’NAAN,

HALEY REINHART, THALIA, EMILY WARREN

MANDARIN ORIENTAL

7:00PM COCKTAILS – LOBBY LOUNGE

8:00PM DINNER AND ENTERTAINMENT – MANDARIN BALLROOM

FESTIVE ATTIRE

————————————————————————

PAGE 2 — REPLY / RSVP CARD

————————————————————————

DUBIN BREAST CENTER SECOND ANNUAL BENEFIT

MONDAY, DECEMBER 10, 2012

HONORING

ELISA PORT, MD, FACS AND THE RUTTENBERG FAMILY

MANDARIN ORIENTAL, NEW YORK CITY

PLEASE ADD MY NAME TO THE BENEFIT COMMITTEE AND RESERVE THE FOLLOWING:

[ ] ONE PLACE TABLE AT $100,000

Table for 10 at dinner with priority seating, special recognition

during the evening, One Place listing in the printed program,

listing on Dubin Breast Center Annual and Permanent Donor Walls

and Diamond Circle benefits of the Dubin Breast Center Circle

of Friends.

[ ] ONE MISSION TABLE AT $50,000

Table for 10 at dinner with premium seating, special recognition

during the evening, One Mission listing in the printed program,

listing on Dubin Breast Center Annual Donor Wall and Platinum

Circle benefits of the Dubin Breast Center Circle of Friends.

[ ] ONE TEAM TABLE AT $25,000

Table for 10 at dinner with excellent seating, One Team listing

in the printed program, listing on Dubin Breast Center Annual

Donor Wall and Gold Circle benefits of the Dubin Breast Center

Circle of Friends.

[ ] ONE PURPOSE TABLE AT $10,000

Table for 10 at dinner, One Purpose listing in the printed

program, listing on Dubin Breast Center Annual Donor Wall and

Silver Circle benefits of the Dubin Breast Center Circle of

Friends.

[ ] ONE ROOF INDIVIDUAL TICKET(S) AT $2,500

Priority seating for dinner and One Roof listing in the printed

program.

[ ] ONE INDIVIDUAL TICKET(S) AT $1,000

Seating for dinner and One listing in the printed program.

Please make checks payable to Dubin Breast Center

(Tax-ID# 13-6171197)

Return to Event Associates, Inc.,

162 West 56th Street, Suite 405, New York, NY 10019.

Your contribution less $275 per ticket is tax-deductible.

NAME: _________________________ COMPANY: _________________________

ADDRESS: _______________________ CITY: ________ STATE: __ ZIP: ____

E-MAIL: _______________________ PHONE: ________ FAX: _____________

CREDIT CARD: [ ] Visa [ ] MasterCard [ ] AmEx

CARD NUMBER: ___________________ EXP. DATE: ________

CARDHOLDER SIGNATURE: __________ TOTAL $ ________

For further information, please contact Debbie Fife:

Phone: 212-245-6570 ext. 20

Fax: 212-581-8717

E-mail: dubinbreastcenter@eventassociatesinc.com

Website: http://www.dubinbreastcenter.org

DUBIN BREAST CENTER BENEFIT COMMITTEE:

PAULINE DANA AND RAFFI ARSLANIAN

MICHELE AND TIMOTHY BARAKETT

LISA AND JEFF BLAU

ANN COLLEY

JULIE ANNE QUAY AND MATTHEW EDMONDS

LISE AND MICHAEL EVANS

EILEEN PRICE FARBMAN AND STEVEN FARBMAN

TANIA AND BRIAN HIGGINS

LAURA KRUPINSKI

MARCY AND MICHAEL LEHRMAN

CHRISTINE MACK

ALICE AND LORNE MICHAELS

THALIA AND TOMMY MOTTOLA

DORE HAMMOND AND JAMES NORMILE

ANN O’MALLEY

TRISH PALIOTTA

BETH AND JASON ROSENTHAL

CAROLYN AND CURTIS SCHENKER

LESLEY AND DAVID SCHULHOF

LYNN AND STEPHAN SOLOMON

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION, CALL 212-245-6570

DUBINBREASTCENTER@EVENTASSOCIATESINC.COM

http://WWW.DUBINBREASTCENTER.ORG

========================================================================

RECOVERY METHOD — TECHNICAL DETAILS

THE PROBLEM

EFTA00400459.pdf is a 76-page scanned document from the Epstein DOJ

Dataset 9. The DOJ printed the original email (which contained a MIME

base64-encoded PDF attachment), then scanned it back as a PDF image with

an OCR text layer. The OCR text layer contains the base64 data, but with

significant character-level errors introduced by OCR misreading the

Courier New monospace font.

Root cause: Courier New renders 1, l, and I nearly identically. Same

for 0 and O. The OCR engine also inserted spurious characters (periods,

commas, parentheses, hyphens, etc.) and frequently miscounted character

widths, producing lines that were too long or too short.

————————————————————————

WHAT FAILED (19 APPROACHES)

————————————————————————

# | Approach | Result

—-+—————————————–+—————————

1 | Strip invalid chars from original OCR | Misaligns byte boundaries

2 | Substitute common OCR errors | Makes corruption worse

3 | Brute-force character scoring | Combinatorial explosion

4 | qpdf repair on decoded PDF | Cannot fix stream corruption

5 | pikepdf repair | Same — structural only

6 | Ghostscript render | Crashes on corrupt streams

7 | mutool clean | Cannot repair

8 | pdfimages extract | No images in decoded PDF

9 | pdftoppm render | Fails on corrupt streams

10 | pdftotext extract | No text extractable

11 | XMP thumbnail extract | No thumbnail embedded

12 | Exhaustive zlib scan across raw bytes | No valid headers found

13 | Per-line decode of original OCR text | 276,024 bytes, 0/40 streams

14 | OCR error correction + brute-force zlib | 23-45% corruption, too deep

15 | inflateSync (zlib sync recovery) | No flush points in CS4

16 | DEFLATE sync point scanning | Only garbage found

17 | Tesseract re-OCR with char whitelist | WORSE: 9% good vs 65%

18 | KoKuToru templates on wrong resolution | 2% byte match

19 | Partial zlib decompression attempts | 0 bytes from any stream

————————————————————————

DETAILED BREAKDOWN OF FAILED APPROACHES

————————————————————————

Below is what we actually ran for each approach, why it failed, and the

lesson learned. Included so you don’t repeat our mistakes.

APPROACH 1-2: CLEANING THE ORIGINAL OCR TEXT LAYER

The EFTA00400459.pdf already has an OCR text layer embedded by the DOJ’s

scanning process. We extracted it with:

pdftotext EFTA00400459.pdf efta_text.txt

The base64 data starts at line 10 (after MIME headers) and runs through

line 4852. Line 4853 is the MIME boundary. Stats on the extracted text:

– 4,843 base64 lines total

– 3,161 lines (65.3%) had exactly 76 valid base64 characters

– 1,554 lines had wrong length (1,253 too long, 301 too short)

– 262 invalid characters found: periods, commas, parentheses, hyphens

Approach 1 — Strip invalid characters: Removed all non-base64 chars

from each line. Problem: this changes line lengths, so when you

concatenate and decode, the byte boundaries shift. Every error cascades

forward, corrupting everything after it.

Approach 2 — Substitute OCR errors: Mapped common misreads (period to

+, comma to /, etc.) based on Courier New visual similarity. This was a

guess and made things worse — the substitutions were wrong more often

than right, and still didn’t fix length errors.

Lesson: You cannot fix OCR errors by post-processing the text. The

character-level accuracy is too low and the errors are too varied

(insertions, deletions, substitutions all mixed together).

APPROACH 3: BRUTE-FORCE CHARACTER SCORING

Attempted to score every possible character at each position using base64

validity and zlib checksum feedback. For a single 76-character line with

even 5 errors, the search space is 64^5 = ~1 billion possibilities. With

1,554 corrupted lines, this is computationally intractable.

Lesson: Brute-force correction cannot work when corruption exceeds ~2

characters per line.

APPROACH 4-11: PDF REPAIR AND EXTRACTION TOOLS

After per-line decoding the original OCR text (Approach 13 below), we

got a file with a valid PDF header but corrupt streams. We threw every

PDF tool at it:

qpdf –recover DBC12_perline.pdf DBC12_repaired.pdf

>> “unable to find /Root dictionary” — structural damage too deep

pikepdf.open(‘DBC12_perline.pdf’)

>> Opens but all streams still corrupt, no content extractable

gs -dNOPAUSE -dBATCH -sDEVICE=png16m -r150 -sOutputFile=page_%d.png

>> Crashes on corrupt FlateDecode streams

mutool clean DBC12_perline.pdf DBC12_mutool.pdf

>> “error: zlib error: invalid stored block lengths”

pdfimages -png DBC12_perline.pdf decoded_images/img

>> 0 images extracted — PDF contains vector graphics, not raster

pdftoppm -png DBC12_perline.pdf decoded_pages/page

>> Fails with stream decompression errors

pdftotext DBC12_perline.pdf –

>> Empty output — can’t read text from corrupt streams

pikepdf — checked pdf.Root.keys() for /Thumb key

>> No thumbnail embedded

Lesson: PDF repair tools fix structural issues (missing xref tables,

broken object references). They CANNOT fix byte-level corruption inside

compressed streams. If the zlib data is wrong, no PDF tool can help —

you need to fix the source data.

APPROACH 12: EXHAUSTIVE ZLIB SCAN

Scanned the entire raw decoded file for valid zlib headers (byte 0x78

followed by valid compression flags) and attempted decompression at

every offset:

for i in range(len(data)):

if data[i] == 0x78 and data[i+1] in [0x01, 0x5E, 0x9C, 0xDA]:

try: zlib.decompress(data[i:])

except: pass

Result: Found zlib headers at the expected positions (matching “stream”

markers in the PDF structure) but every single one failed decompression.

The corruption is distributed throughout each stream, not localized.

APPROACH 13: PER-LINE INDEPENDENT BASE64 DECODE (BEST PRE-BREAKTHROUGH)

The key insight: MIME base64 uses 76-character lines, and each line

decodes independently to exactly 57 bytes. So instead of concatenating

all base64 and decoding as one block (where one error corrupts everything

after it), decode each line separately:

for line in b64_lines:

cleaned = keep only valid base64 chars

if len(cleaned) == 76:

chunks.append(base64.b64decode(cleaned))

else:

chunks.append(null_bytes * 57) # placeholder

Result: 276,024 bytes. Valid PDF header (%PDF-1.5). Correct metadata

readable. But 0 out of 40 FlateDecode streams could decompress — even

though 65% of lines decoded correctly, the remaining 35% corrupt lines

are scattered throughout every stream, and zlib requires bit-perfect

data.

This was our best result for months and the baseline we compared

everything else against.

APPROACH 14: OCR ERROR CORRECTION + BRUTE-FORCE ZLIB VALIDATION

Analyzed corruption patterns in each stream:

Stream 1: 6 lines, 2 corrupt (33%)

Stream 5: 67 lines, 15 corrupt (22%)

Stream 6: 67 lines, 30 corrupt (45%)

… average 23-45% corrupt lines per stream

Then attempted to fix corrupt lines by trying all possible single-

character substitutions and checking if zlib decompression succeeded.

Result: With 15-30 corrupt lines per stream and unknown error types

(insertion, deletion, substitution), the search space is astronomical.

Even single-character fixes per line didn’t help because most lines had

multiple errors. The corruption is too deep for algorithmic correction.

APPROACH 15: INFLATESYNC (ZLIB BUILT-IN RECOVERY)

Zlib has a Z_SYNC_FLUSH mechanism that allows recovery after corruption

by finding sync points. We tried it.

Result: Adobe Illustrator CS4 (which created this PDF) does not insert

sync flush points in its DEFLATE streams. The entire stream is one

continuous DEFLATE block with no recovery points. inflateSync only works

if the compressor used Z_SYNC_FLUSH at regular intervals, which most PDF

producers do not.

Lesson: inflateSync is useless for PDF FlateDecode streams. It’s

designed for streaming protocols (like HTTP chunked encoding), not file

formats.

APPROACH 16: DEFLATE SYNC POINT SCANNING (ACADEMIC METHOD)

Based on the paper “Reconstructing corrupt DEFLATEd files” (DFRWS 2011),

we scanned the raw DEFLATE bitstream for natural sync points — positions

where the DEFLATE decoder could re-synchronize:

– Scanned for non-compressed blocks (BTYPE=00) with validatable lengths

– Scanned for fixed Huffman blocks (BTYPE=01) with known code tables

– Scanned for dynamic Huffman blocks (BTYPE=10) with code table headers

– Scanned all 40 streams at bit-level granularity

– Found 3 potential non-compressed block markers

Result: Only recovered 86 bytes of repetitive garbage data (likely false

positives). The DEFLATE streams in this PDF are predominantly dynamic

Huffman blocks with no non-compressed segments. The academic technique

works best for large files with mixed block types — a 2-page PDF

invitation doesn’t have enough data for natural sync points to occur.

APPROACH 17: TESSERACT RE-OCR WITH CHARACTER WHITELIST

Re-OCR’d the source page images using Tesseract 5 with a strict

character whitelist limited to valid base64 characters:

tesseract page_001.png stdout –psm 6 \

-c “tessedit_char_whitelist=A-Za-z0-9+/=> ” \

-c “preserve_interword_spaces=1”

Ran this on all 75 base64 pages.

Result: Only 9% of lines were exactly 76 characters — dramatically

worse than the original OCR text layer (65%). The whitelist forces

Tesseract to map every pixel region to a base64 character, but it causes

massive character insertion. Where the original OCR might output “1l”

(two characters), whitelisted Tesseract outputs “1ll1” (four characters)

because it’s trying to fill every pixel region with a valid character.

Original OCR: 3,161/4,843 lines at 76 chars (65.3%)

Tesseract re-OCR: ~450/5,000+ lines at 76 chars (9%)

Lesson: Character whitelisting makes OCR worse for this use case, not

better. The Tesseract engine’s character segmentation is the problem,

not its character classification. Whitelisting doesn’t fix segmentation.

APPROACH 18: KOKUTORU TEMPLATES ON WRONG RESOLUTION

Our first attempt at running the KoKuToru template matcher used images

extracted by PyMuPDF at 300 DPI (2448×3168 pixels) instead of the native

pdfimages resolution (816×1056 pixels). The KoKuToru templates are

calibrated for the exact native scan resolution.

Result: Only 2% of bytes matched between KoKuToru output and original.

The templates are pixel-exact for 816×1056 images — using any other

resolution produces garbage because the character grid doesn’t align.

Lesson: Use pdfimages (poppler-utils) to extract at native resolution,

NOT PyMuPDF/pdf2image at a custom DPI. The template matcher requires

exact pixel alignment.

APPROACH 19: PARTIAL ZLIB DECOMPRESSION

Attempted to decompress each stream and capture whatever bytes came out

before the error:

d = zlib.decompressobj(15)

partial = d.decompress(stream_data) # catch error, keep partial

Result: 0 bytes from every stream. The corruption occurs so early in

each stream (within the first few hundred bytes) that zlib cannot

decompress even a single byte before hitting an error. This confirms

that the corruption is uniformly distributed, not concentrated at the

end.

ALSO TRIED: VISION LLM OCR (QWEN3 VL 32B INSTRUCT)

Sent each page image to a Qwen3 VL 32B vision model via a local

LMStudio endpoint, asking it to read the base64 characters:

POST http://endpoint:5000/v1/chat/completions

model: qwen3-vl-32b-instruct

Prompt: “Extract every line of base64 text exactly as it appears…”

Processed 4 pages concurrently

Result: ~30% of lines at exactly 76 characters. Better than Tesseract

(9%) but far below KoKuToru template matching (99.96%). The vision model

understands the concept of base64 and tries hard, but its character-

level accuracy on 8-pixel-wide Courier New glyphs is not sufficient. It

frequently confuses 1/l/I, 0/O, +/t, v/y, m/rn.

Also tested LightOnOCR 1B (a smaller specialized OCR model) — produced

mostly garbage output, repeating character patterns.

Lesson: Current vision LLMs are not accurate enough for character-perfect

OCR of monospace base64 text. Template matching (pixel-level comparison

against known glyph images) vastly outperforms neural approaches for this

specific task because it doesn’t need to “understand” the text — it just

needs to match exact pixel patterns.

————————————————————————

WHAT WORKED

————————————————————————

KoKuToru template-matching OCR — a pixel-level character recognition

approach specifically designed for this exact problem.

Step 1: Extract Raw Page Images

pdfimages -png EFTA00400459.pdf pdfimages_out/img

>> Produces 76 grayscale PNG images (816×1056 pixels each)

>> Image 0 = email header page (skip)

>> Images 1-75 = base64 content pages

Step 2: Build Character Templates

The KoKuToru approach uses 342 individual character template images

(8×12 pixels each) representing every glyph that appears in Courier New

base64 text at this specific scan resolution. Templates are named

letter__.png (e.g., letter_A_0.png, letter_a_0.png —

REQUIRES A CASE-SENSITIVE FILESYSTEM).

On macOS, a case-sensitive APFS disk image is required:

hdiutil create -size 50m -fs “Case-sensitive APFS” \

-volname CaseSensitive casesensitive.dmg

hdiutil attach casesensitive.dmg

Step 3: Template-Matching OCR

Grid parameters:

letter_w = 8 pixels

cell_w = 8 – 1/5 = 7.8 pixels (sub-pixel spacing)

letter_h = 12 pixels

line_h = 12 + 3 = 15 pixels (line spacing)

y_start = 39 pixels (top margin to first text line)

x_start = 61 pixels (left margin, after “> ” prefix)

Image preprocessing:

pixel = round(pixel * 64) / 64 (quantize to reduce noise)

Matching algorithm:

For each character position in the grid:

Extract 8×12 pixel region from the page image

Compare against all 342 templates using L1 loss

Select the template with minimum L1 loss

Output the corresponding character

Output newline every 76 characters

Tool: https://github.com/KoKuToru/extract_attachment_EFTA00400459

Step 4: Per-Line Independent Base64 Decode

Each 76-character base64 line decodes independently to exactly 57 bytes.

This is the key insight — MIME base64 was designed so each line is self-

contained, meaning errors on one line don’t propagate.

Step 5: Validate via FlateDecode Stream Decompression

The ultimate test: can zlib decompress the PDF’s embedded streams?

KoKuToru OCR result: 39/40 streams decompressed (97.5%)

Original OCR result: 0/40 streams decompressed (0%)

Tesseract re-OCR: 0/8 streams decompressed (0%)

Qwen3 VL 32B: 0 streams decompressed (0%)

Step 6: Extract Text from Content Streams

Decompressed streams contain PDF content operators. Text was extracted by

parsing TJ and Tj operators:

TJ operator: array of strings and kerning values

Example: [(PLEASE ) -20 (JOIN)] TJ

Tj operator: single string

Example: (MANDARIN ORIENTAL) Tj

————————————————————————

RECOVERY STATISTICS

————————————————————————

Source document: EFTA00400459.pdf (76 pages, 11.25 MB)

Base64 lines in source: 4,843

KoKuToru lines at 76 chars: 4,840 (99.96%)

Original OCR at 76 chars: 3,161 (65.3%)

Decoded PDF size: 275,971 bytes

Expected PDF size: 276,028 bytes

Size difference: 57 bytes (1 base64 line — corrupt first line)

FlateDecode streams found: 40

Streams decompressed: 39 (97.5%)

Total decompressed data: ~500 KB

Text content recovery: 100% of both pages

————————————————————————

TOOLS USED

————————————————————————

– pdfimages (poppler-utils) — raw image extraction from scanned PDF

– KoKuToru/extract_attachment_EFTA00400459 — template-matching OCR

engine (Python, PyTorch)

– Python standard library — base64 decoding, zlib decompression

– Custom scripts — PDF content stream parsing, text extraction

– macOS case-sensitive APFS disk image — required for template filenames

ALSO TESTED (NOT USED IN FINAL RECOVERY)

– Qwen3 VL 32B Instruct (vision LLM) — 30% good lines

– LightOnOCR 1B — too small, produced garbage

– Tesseract 5 with character whitelist — 9% good lines

– voronaam/pdfbase64tofile (Rust interactive corrector) — manual

– HarryR/GhettoOCR (PHP fixed-width OCR) — less refined

– DEFLATE sync point reconstruction (DFRWS 2011) — no flush points

========================================================================

HOW TO REPRODUCE THIS RECOVERY (STEP-BY-STEP)

If you want to independently verify or reproduce this recovery, follow

these instructions exactly.

PREREQUISITES

Operating System: macOS, Linux, or Windows (WSL)

Python: 3.8+

Storage: ~500 MB free space

Install dependencies:

# System packages (macOS with Homebrew)

brew install poppler # provides pdfimages

# Python packages

pip install torch torchvision Pillow

If on macOS — you need a case-sensitive filesystem because the KoKuToru

templates have filenames like letter_A_0.png and letter_a_0.png which

collide on macOS’s default case-insensitive HFS+/APFS. Linux users can

skip this.

hdiutil create -size 50m -fs “Case-sensitive APFS” \

-volname CaseSensitive casesensitive.dmg

hdiutil attach casesensitive.dmg

# Working directory: /Volumes/CaseSensitive/

STEP 1: OBTAIN EFTA00400459.pdf

Download EFTA00400459.pdf from Epstein DOJ Dataset 9. This is the

76-page scanned email document (11.25 MB). Verify:

$ file EFTA00400459.pdf

EFTA00400459.pdf: PDF document, version 1.6

$ ls -la EFTA00400459.pdf

# Should be approximately 11,796,482 bytes (11.25 MB)

$ pdfinfo EFTA00400459.pdf

Pages: 76

STEP 2: EXTRACT RAW PAGE IMAGES

mkdir -p pdfimages_out

pdfimages -png EFTA00400459.pdf pdfimages_out/img

This produces 76 PNG files: img-000.png through img-075.png.

Verify:

$ file pdfimages_out/img-000.png

PNG image data, 816 x 1056, 8-bit grayscale, non-interlaced

$ ls pdfimages_out/ | wc -l

76

img-000.png = email header page (NOT base64 — skip this)

img-001.png through img-075.png = base64 content pages

STEP 3: CLONE AND SET UP KOKUTORU TEMPLATE-MATCHING OCR

# On macOS, clone to case-sensitive volume:

cd /Volumes/CaseSensitive/

git clone https://github.com/KoKuToru/extract_attachment_EFTA00400459.git

cd extract_attachment_EFTA00400459

# Verify templates exist (342 PNG files in letters_done/)

ls letters_done/ | wc -l

# Should be 342

The repo contains:

– ocr.py — the template-matching OCR engine

– letters_done/ — 342 character template PNGs (8×12 pixels each)

– Each template is named letter__.png

STEP 4: RUN TEMPLATE-MATCHING OCR ON EACH PAGE

Copy your extracted page images (skip img-000) into the KoKuToru

directory and run the OCR:

cp /path/to/pdfimages_out/img-001.png … img-075.png ./

python3 ocr.py

The output is a text file with one base64 line per 76 characters.

Verify your OCR output:

wc -l base64_extracted.txt

# Expected: ~4842

awk ‘{ print length }’ base64_extracted.txt | sort | uniq -c | sort -rn | head

# The vast majority should be 76

STEP 5: HANDLE THE FIRST LINE

The first page of base64 (img-001.png) contains the PDF header line

starting with JVBERi0xLjU (which decodes to %PDF-1.5). The KoKuToru

OCR may start at line 2 because the first page also has email header

text above the base64 block.

Check if the first line is present:

head -1 base64_extracted.txt

# Should start with JVBERi0 (= %PDF-)

# If it doesn’t, you need to prepend it

If the first line is missing, extract it from the original OCR text:

pdftotext EFTA00400459.pdf – | grep “JVBERi0” | head -1

STEP 6: FIND AND REMOVE THE MIME BOUNDARY

The base64 data ends before the MIME boundary. Check the end:

tail -10 base64_extracted.txt

# Remove any lines containing _002_, cpusers, carillon, or CECCBD6

STEP 7: DECODE BASE64 TO PDF (PER-LINE METHOD)

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import base64

VALID_B64 = set(“ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789+/=”)

with open(“base64_extracted.txt”) as f:

lines = [line.strip() for line in f if line.strip()]

# Remove MIME boundary lines at end

while lines and any(x in lines[-1] for x in [‘_002_’, ‘cpusers’, ‘carillon’]):

lines.pop()

chunks = []

good = 0

for i, line in enumerate(lines):

cleaned = “”.join(ch for ch in line if ch in VALID_B64)

is_last = (i == len(lines) – 1)

if is_last:

r = len(cleaned) % 4

if r: cleaned += “=” * (4 – r)

try:

chunks.append(base64.b64decode(cleaned))

good += 1

except:

chunks.append(b’\x00′ * 57)

result = b””.join(chunks)

print(f”Decoded: {len(result)} bytes (expected ~276,028)”)

print(f”Good lines: {good}/{len(lines)}”)

with open(“DBC12_recovered.pdf”, “wb”) as f:

f.write(result)

Expected output:

Decoded: 275971 bytes (expected ~276,028)

Good lines: 4842/4842 (100%)

PDF header: b’%PDF-1.5\r%\xe2\xe3\xcf\xd3\r\n’

STEP 8: VALIDATE — DECOMPRESS FLATEDECODE STREAMS

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import zlib

with open(“DBC12_recovered.pdf”, “rb”) as f:

data = f.read()

pos = 0

stream_num = 0

success = 0

while True:

marker = data.find(b’stream’, pos)

if marker < 0: break

cs = marker + 6

while cs < len(data) and data[cs:cs+1] in [b'\r', b'\n']: cs += 1

es = data.find(b'endstream', cs)

if es < 0:

pos = marker + 6

continue

sd = data[cs:es]

stream_num += 1

for wbits in [15, -15, 31]:

try:

dc = zlib.decompress(sd, wbits)

print(f" Stream #{stream_num}: {len(dc)} bytes OK")

success += 1

with open(f"stream_{stream_num}.bin", "wb") as f:

f.write(dc)

break

except: pass

pos = es + 9

print(f"Result: {success}/{stream_num} streams decompressed")

# Expected: 39/40

STEP 9: EXTRACT TEXT FROM DECOMPRESSED CONTENT STREAMS

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import re, glob

def extract_text(data):

text = data.decode('latin-1')

result = []

for m in re.finditer(r'\(([^)]*)\)\s*Tj', text):

result.append(m.group(1))

for m in re.finditer(r'\[(.*?)\]\s*TJ', text):

strings = re.findall(r'\(([^)]*)\)', m.group(1))

result.append("".join(strings))

return result

all_text = []

for sf in sorted(glob.glob("stream_*.bin")):

with open(sf, "rb") as f:

texts = extract_text(f.read())

if texts: all_text.extend(texts)

for line in all_text:

if line.strip(): print(line)

STEP 10: VERIFY AGAINST KNOWN CONTENT

Check for these key strings in the extracted text:

DUBIN BREAST CENTER

SECOND ANNUAL BENEFIT

MONDAY, DECEMBER 10, 2012

MANDARIN ORIENTAL

ELISA PORT, MD, FACS

CYNTHIA MCFADDEN

Tax-ID# 13-6171197

Event Associates, Inc.

162 West 56th Street, Suite 405

212-245-6570

dubinbreastcenter@eventassociatesinc.com

If all of these appear in your extracted text, the recovery is confirmed.

TROUBLESHOOTING

letter_A_0.png and letter_a_0.png collide:

You're on a case-insensitive filesystem. Use a case-sensitive disk

image (macOS) or use Linux.

KoKuToru OCR output starts at line 2:

The first page has email header text above the base64 block. Prepend

the first base64 line from the original OCR text layer.

0 streams decompress:

Your OCR output has too many errors. Check that pdfimages extracted

at the native resolution (816×1056). Do NOT resample or resize

images before running the template matcher.

Only ~65% of lines are 76 chars:

You're using the original OCR text layer, not the KoKuToru template-

matching output. The built-in OCR text layer is too corrupt.

ModuleNotFoundError: torch:

Install PyTorch: pip install torch torchvision

Streams decompress but text is garbled:

The streams may contain font-encoded text with custom ToUnicode

mappings. Check the PDF's font dictionaries for character mapping.

File size differs by exactly 57 bytes:

This is the known first-line issue. The first base64 line (57 decoded

bytes = PDF header) is partially corrupt in all OCR sources.

FILE CHECKSUMS (FOR VERIFICATION)

DBC12_recovered.pdf: ~275,971 bytes

Decompressed streams: 39 files, ~500 KB total

base64_extracted.txt: ~4,842 lines, ~367 KB

————————————————————————

KNOWN LIMITATIONS

————————————————————————

– The first base64 line (containing the PDF header %PDF-1.5) was

partially corrupt in both OCR sources. The original OCR text layer

version was used as a fallback.

– 1 of 40 FlateDecode streams did not decompress — likely the stream

spanning the first-line boundary.

– The reconstructed PDF does not render in standard PDF viewers due to

the 57-byte offset and the one failed stream, but all text content

was successfully extracted from the 39 decompressed streams.

========================================================================

ENJOY!

A lot of the unnamed files that are attached to emails can be converted to text document and opened up a notepad.

Hi, I don’t know anything about programming but I was sent the link to your blog after asking about a specific file in the Epstein library. It’s an email to Epstein containing pages and pages of code which appear to be from the website xvideos. Are you able to have a look at it and see if it’s Source code that’s been shared with him or just a link? (Or something else I suppose?) My immediate thought was that he might have been involved in the backend of that site somehow. Which seems retirement and terrifying.

Here’s the link to the file:

https://www.justice.gov/epstein/files/DataSet 11/EFTA02373294.pdf

Um….don’t see the extension.